Jackie Ineke, Spring’s Chief Investment Officer. Jackie began her career as a bank supervisor at the Bank of England in the 1990s, then set up European financials credit research at SBC Warburg Dillon Read and then moved to UBS with the merger. In 2000 she became Head of European Financials Credit Research at Morgan Stanley, from 2003 running her team from Zurich, where she’s still based. Jackie ‘wrote the book’ on bank credit in 2003 with «Bank Capital A-Z», which became a fixture on every bank investor’s desk. She has been ranked #1 in her field by the Insitutional Investor survey for more than 10 years, until she left Morgan Stanley in 2023. Jackie joined Spring in April 2024.

Zürich, March 2025

Dear Readers,

What follows is a brief introduction to bank bonds and within that, the most yieldy segment, which is Additional Tier 1 bonds. I’ve been analysing banks since 1993, through the Great Financial Crisis and a number of sovereign crises, a global pandemic and a war in Europe. The past fifteen years of that period has been characterised by thousands of pages of bank regulations, which have not only impacted the credit strengths of the banks, but often also how bonds have traded. Here, I’ll simply focus on the characteristics of AT1 bonds alone. At Spring, AT1s are our passion and we’re always delighted to discuss this sector in far greater detail – please do get in touch.

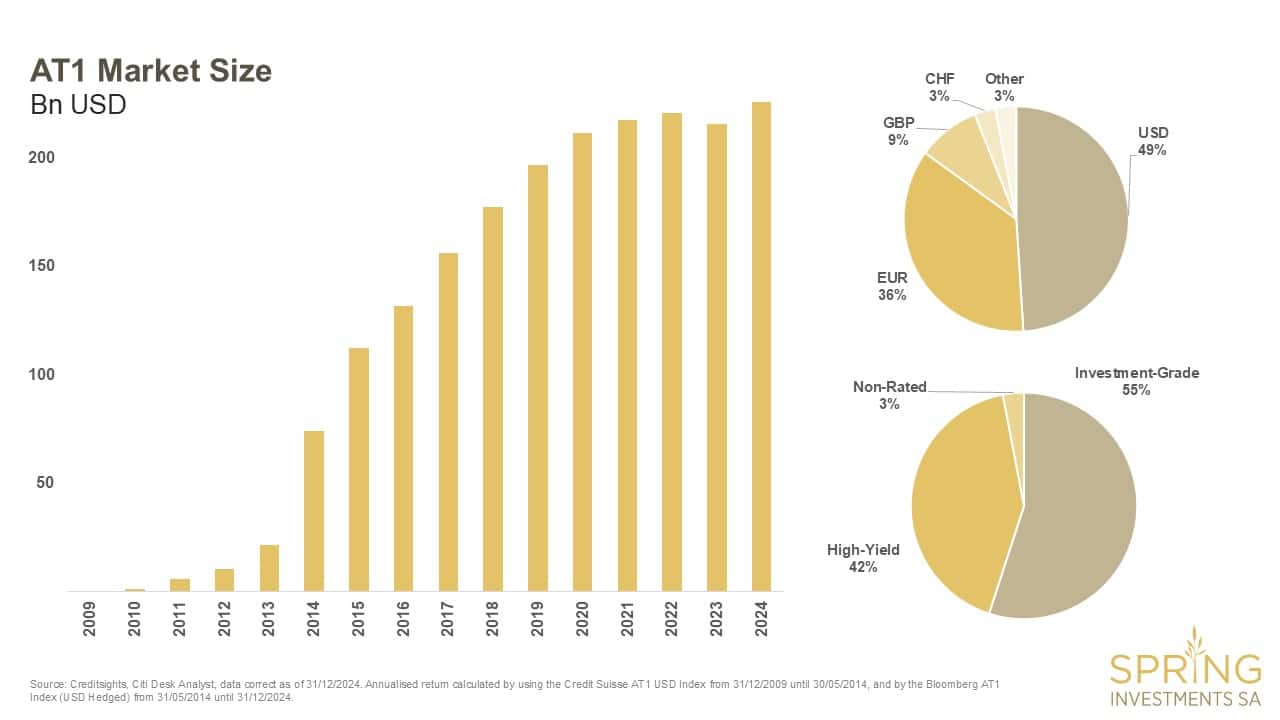

Additional Tier 1 is a type of debt issued by European banks, paying a fixed coupon. It is also known as AT1 for short, and as CoCos – the latter being short for Contingent Convertibles, which is a name linked to the bonds’ structure, which we’ll come back to. AT1s form part of a bank’s liability stack. Banks take in deposits and typically pay a rate of interest on those. These deposits will fund the bank’s assets such as mortgages, unsecured loans and investments in securities. However, it’s extremely rare that a bank’s deposit base is large enough to cover all its activities on the asset side of its balance sheet. As well as taking deposits, a bank will issue debt to finance those assets. There are different forms of debt with senior debt being the cheapest a bank can issue to investors (requiring the lowest coupon), down to AT1s which is subordinated debt, paying the highest coupons. A bank’s debt stack will typically include deposits taken from individuals and corporates, senior debt, subordinated debt (also called Tier 2) and deeply subordinated debt (AT1). Below this debt stack sits a bank’s equity. AT1 is senior to a bank’s equity, but subordinated to all other debt. This fact can appear worrying to bond investors, although as we describe below, AT1 bonds have only faced losses on two occasions in the last fifteen years. In contrast to corporate hybrid bonds, many AT1 bonds are investment-grade rated despite being subordinated, because the banks as issuers of these bonds themselves are very highly rated.

European banks issue AT1 bonds in different currencies, but in USD terms as at March 2025 it’s around USD230 billion. It’s very rare that a single bond is more than $1 billion in size, indicating that there is a vast choice of bonds to invest in. We expect the size of the market to continue to grow for two reasons. First, banks’ balance sheets grow as they lend to private individuals and corporates, supporting a country’s economic growth. The amount of AT1s it makes sense for a bank to issue, is linked to the risk-adjusted size of its assets. Second, many banks have not yet issued AT1s, but are incentivised to do so. Nearly all the very largest banks in Europe issue AT1s already and this market has grown significantly over the past fifteen years.

The cost to a bank of issuing AT1s is much higher than senior debt. At any given time, an investor will receive a much higher yield on an AT1, than if they owned senior bonds of the same bank. Banks issue AT1s because it is a form of bank capital. Banks are heavily regulated in all aspects of their business and what form and size their capital must take, are no exceptions to this. Regulatory guidelines are often globally agreed in very basic terms, and then EU and country-specific bank regulators translate these guidelines into detailed law for their own jurisdictions.

Banks must have a certain level of bank capital. This is considered as a reserve which can typically absorb losses when a bank is in difficulties. The higher the level of capital versus a measure of the bank’s riskiness of its assets, the stronger the bank will appear to be and the higher its credit rating, all else held equal. Capital is not just equity, or as it’s known in regulatory terms, Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1). Banks also have debt capital instruments they can issue. This is made up of Tier 2 and AT1 debt. Senior debt is not bank capital. CET1 will be the most expensive form of capital a bank can issue – this is dilutive to existing shareholders, and will attract a dividend payment, which is paid out of post-tax profits. Debt capital is naturally non-dilutive as it has no voting rights, and coupons are typically paid out of pre-tax income. Supervisors consider CET1 to be the strongest form of capital for a bank, and hence whilst banks can have as much CET1 as they please, the amounts of AT1 and Tier 2 that are recognised as capital by a bank, are limited to certain maxima which are set by bank supervisors.

The bottom line here is that if a bank has not issued enough AT1 to meet its maximum regulatory allowance, then it has to hold the balance in CET1 – which is more expensive and dilutive. A bank would always rather issue AT1 than CET1. This brings us back to our comment above, that as time goes on, all European banks will issue AT1 bonds, if they have not done so already.

In very simplistic terms, if a bank has $100bn in risk-weighted assets (a regulatory-defined measure of risk on the bank’s balance sheet) and has a 12% total Tier 1 requirement from its bank supervisor, then it could issue $12bn of equity, or $11bn of equity and $1bn of cheaper, non-dilutive AT1s. In both cases, its Tier 1 ratio would be 12% but in the latter case, it has met this requirement more cheaply and with less dilution for shareholders.

If you’re as old as I am, you’ll recall that banks’ balance sheets around the world suffered heavily in the GFC, with losses in the USD hundreds of billions. Up to this point, the way to deal with failed banks was to declare them bankrupt and place them in liquidation, with bondholders lining up ahead of shareholders and behind depositors, to wait and hope for their money back. The GFC was different. This was a global, systemic financial crisis. Dealing with a single, small bank which fails by itself is quite different to when the global banking system is under threat. Economies need strong, healthy banks to continue to lend and to pull those economies out of downturns. Lehman Brothers, the first large victim of the GFC in 2008, was put into liquidation – and that took fourteen years to play out. Any further liquidations post Lehman were not an option.

Without the possibility of liquidation – which would have hurt economies even more and spread more fear about banks – governments had no option but to keep banks alive through public support. This took many forms, but often included guaranteeing a bank’s funding and providing support packages linked to close-to-worthless assets that the banks owned. Public support essentially means using or promising taxpayers’ money to prop up the banks. New laws had to be passed every day as the crisis was unfolding and whilst some banks were nationalised, this wiped- out shareholders only. In the vast majority of cases, if bank bondholders held onto their bonds throughout the (extreme) volatility in 2009, they ultimately got all their principal back, when the bonds reached maturity.

From the perspective of a bank regulator, instead of governments being forced to use taxpayers’ money to support banks, far more acceptable would have been the ability to force bank bonds to be written down, after equity had absorbed the first part of any losses. Bonds are a liability on a bank’s balance sheet. If you write them down to zero, or forcibly exchange them into equity, then a bank is re-capitalised (essentially, re-equitised after the original equity has first been wiped out, due to absorbing losses).

Bank regulations were already under review before the GFC started, and were naturally turbo-charged once the crisis was in full force. Regulators wanted to design a bond instrument which, if a bank suffered losses, those bonds would be written-down or equitised. To this end, in 2009 AT1s were designed to be “going-concern instruments”. When a bank suffers losses, its CET1 ratio drops as equity absorbs those losses. Regulators decided that when a bank’s CET1 ratio hits a certain level, then AT1s would then be written down or equitised, re-capitalising the bank. The bank would then be open for business the following day, with a still-strong CET1 ratio, despite the losses it just suffered. It would remain a going concern. The public would keep confidence in the bank as its capital ratio had not deteriorated, and the bank would continue operations. At no stage in this thought process would the bank fail. The bank suffers a hiccup but remains a going concern, due to losses being absorbed by the equityholders but then also the bondholders. Taxpayers’ money is protected.

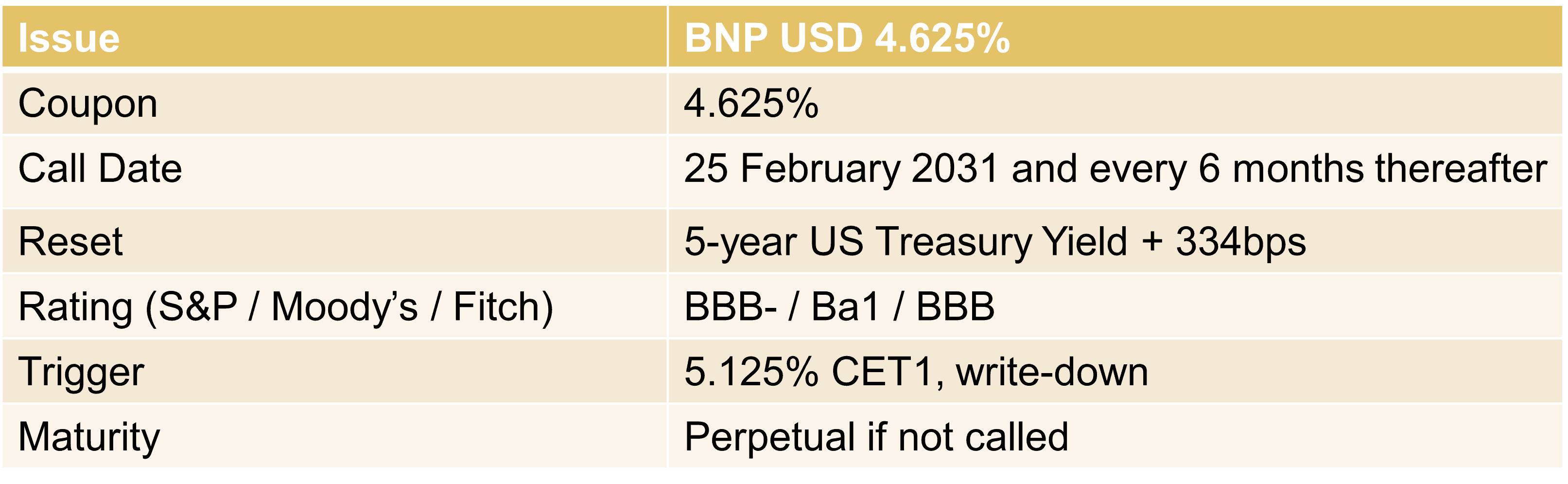

Here we have the ‘Conditional Convertible’ feature, or CoCo feature of AT1s. In 2007, just ahead of the GFC, banks’ capital ratios were low. One of the strongest banks in Europe then, France’s BNP, had a CET1 ratio of around 5.8%. To create a new bank regulation, all the nations of the EU have to agree, and considering BNP’s CET1 ratio, the negotiated CET1 ratio at which an AT1 would be written-down or equitised was set at 5.125%. To put this into context, BNP would have had to make a €4bn loss to see its CET1 drop to 5.125%. This creates a CoCo. A Conversion (either to equity or to zero) was Contingent on the equity ratio (CET1) trigger of 5.125% being hit. Considering BNP’s balance sheet size of €1.7 trillion at the time, there was far from a negligible risk of this happening.

The first way AT1s can get written down or equitized is if the trigger of 5.125% is hit. Back in 2009 when AT1s were created by the regulators, AT1s looked extremely risky. Every investor had very fresh memories of banks making enormous losses and at this time, banks still had equity ratios not so far above the AT1 trigger levels, as we’ve detailed for BNP, above. Memories of the GFC were still very fresh. The first AT1s were issued by only the largest, strongest banks, and even then they had low double-digit fixed coupons, to attract investors. The first investors were essentially only hedge funds. Very few traditional investors felt they could buy AT1s, considering the high risk of the trigger being hit, and the investment being written down to zero or equitised at a very penal rate.

However, this is only the beginning of the AT1 story. These bonds were defined in regulations in 2009, created as the global banking sector was still on its knees and many of the largest banks in Europe were still being rescued by governments. The immediate reaction from regulators was to create a form of debt that could absorb large losses at a bank, if anything like the GFC was to occur again. That box got ticked with the creation of AT1s.

From that point on, everything changed for banks and for AT1s as a “risky” debt class.

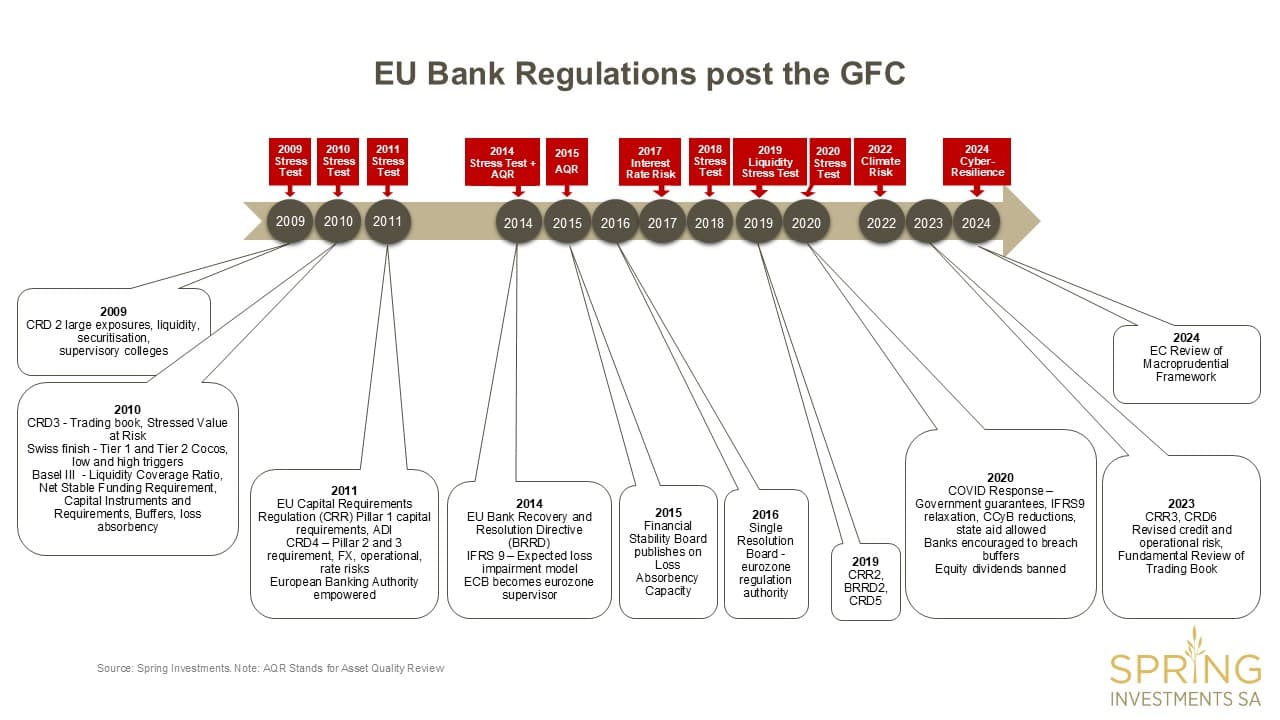

Once regulators in 2009 had created a bond that would absorb losses they set about making the banking sector strong. Strong enough so that a GFC could never happen again and economies could never be at the mercy of a failing banking sector. The banking sector had been humbled and regulators set about making this one of the most highly-regulated industries in the world. Fifteen years of relentless regulations followed the GFC. These included capital, risk management, Level 3 assets, securitisation, liquidity, trading book definitions and risks, recovery and resolution, stress tests, asset quality reviews, provisioning, asset quality definitions, operational and foreign exchange risks, interest rate and climate risks and most recently, cyber security.

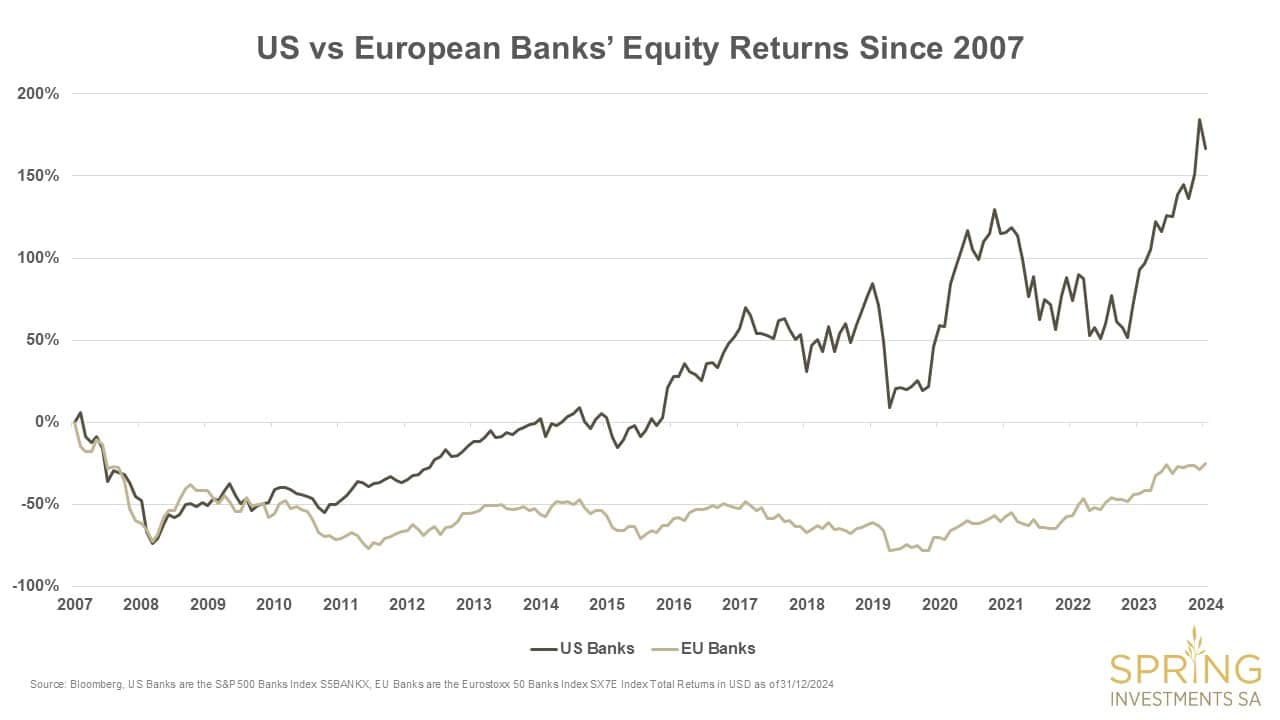

Regulators were, in essence, now working for bank creditors. Essentially, by making the banks as safe as possible, they were ensuring that the risk of loss for bondholders (and of course, depositors) was as low as possible, whilst still allowing the banks to be somewhat profitable. Credit ratings rose over this time but the devastation on European bank stocks was inevitable. As banks were forced to double, triple and even quadruple their equity levels, so their returns on that equity fell. European bank shareholders simply did not know what regulations were coming next and ultimately, this was a process that lasted fifteen years – with a very telling impact on share prices. E

As we noted above, one of the strongest European banks, BNP, had a CET1 ratio of 5.8% in 2007. According to the latest European Banking Authority’s risk-assessment report, the average CET1 of European banks at end 2023 was the highest it’s ever been, at 16.1%.

The AT1 trigger level of 5.125% has never been reviewed. It is now totally irrelevant. No bank has ever hit its AT1 trigger.

Five years after AT1s were hastily designed by the regulators to re-equitise a bank after sudden, significant losses, the same regulators had time to look at the problem of failing banks in a more holistic way. A failing bank needs to be dealt with rapidly and confidence in the banking sector quickly restored, and in 2014, regulators came up with the toolbox.

The EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive set out how a bank is dealt with, when it is failing or likely to fail. There are initially a number of options open to the bank, such as raising more equity or selling operations to boost its capital. Ultimately though, if a bank is deemed to be failing, then supervisors can write down capital instruments – equity, AT1s and Tier 2s. With the GFC as the exception to the rule, banks typically fail due to a loss of confidence which leads to a run on deposits, rather than suffering massive losses. Hence banks fail with plenty of capital – they simply run out of liquidity to meet outflows. Again, no AT1 trigger has been hit. It’s important to note that once capital has been written down, if the resolution authority believes the bank is not yet stabilised, then it will declare the bank is in resolution and can write down or equitise further layers of debt, eating into senior debt (non-preferred senior debt then preferred senior debt). Essentially, the most senior level of debt to face some level of equitisation would become the owner of the bank. The original shareholders are wiped out.

In reality, of the two instances where AT1s have been written down, the bank has been sold to a larger, stronger bank following the ‘resolution weekend’. In 2017, Banco Popular saw all possible write-downable debt written down (including its AT1s) and it was then sold to Banco Santander for €1. In 2023, Credit Suisse saw its AT1s written down, then sold to UBS. This appears to be the safest way to restore confidence in a failing bank – to sell it to a far stronger competitor.

In the two cases where AT1 principal has been lost, the banks were failing. In the EU, equityholders were wiped out and also more senior levels of debt were wiped out. In Switzerland, only AT1s were wiped out (as they should, if the bank is failing), but this was a special, Swiss-specific situation, which we will return to later.

Regulations detail what structure AT1 bonds can take. They are designed to be potentially perpetual. They have a fixed coupon until the first call date, which is set at least five years after issuance. This coupon can thoeretically be skipped by the bank’s management, but we can think of only one instance where this has happened and that was linked to legacy bonds of a German Landesbank – entirely unrepresentative of the AT1 sector today. The supervisor can require coupons to be skipped, but this has never happened. Indeed, during COVID, EU supervisors asked banks to skip paying dividends – but went out of their way to detail why they did not want banks to skip AT1 coupons. There are also two further circumstances when banks must skip coupons, linked to the level of capital and of reserves at the bank. No coupons have ever been skipped in this way. In reality, skipping a coupon is considered a sign of severe weakness in a bank and management will go to any lengths to avoid it. Both Banco Popular and Credit Suisse paid AT1 coupons all the way up to failure. Skipping a coupon could have led to terrific (earlier) pressure on the banks’ share price, or triggered (earlier) increased deposit outflows, as the market would take a skip as a sign of near-failure. Coupons are not cumulative.

When an AT1 bond is issued, the fixed coupon is expressed as a risk-free rate plus a credit spread. At the first call date, the bank can call the bonds back at par. If the AT1s are not called, the fixed coupon is then reset. This again is a measure of the then-current risk-free rate, plus the original credit spread.

If the expected credit spread on a new AT1 bond is lower than if the bank were to not call its AT1s and leave them outstanding, then the bank will naturally call the outstanding AT1 and reissue a new, cheaper (in terms of credit spread) AT1. If the likely cost of reissuing an AT1 bond is higher than leaving the current AT1 outstanding, then the bank must take a decision. In reality, around 95% of all AT1 bonds are called at the first call date. Most banks like to show strength to investors in this way. If not called, the next call dates vary from the bonds being able to be called at any time, to five-year intervals. When considering an investment in an AT1, this extension risk can be measured and priced, when thinking about a bond’s likely yield.

AT1 bonds have a CoCo feature. Many simply have write-down language – if the trigger is hit, then the bonds are written down to zero. Others have an equity settlement feature – if the trigger is hit, bondholders receive equity of the bank. To be clear, the calculation for this equity delivery ensures that any equity received is negligible. Further, if the bank is in serious trouble (which it will be if CET1 is at 5.125%), then we believe that it will be placed into resolution, in any case. This means further layers of debt will be written down and/or equitised – fully wiping out any existing shareholders (whether the original shareholders, or the subsequent AT1 holders who have been equitised). The bottom line is – if a bank is failing or likely to fail, then the AT1s bonds are worthless. Again, this has happened just twice since the birth of AT1s in 2009.

Two banks have had AT1s written down, since AT1s were created in 2009. Banco Popular of Spain – in the EU – happened in 2017 and followed resolution rules. Credit Suisse of Switzerland – not in the EU – happened in 2023 and was more contentious. In both cases, the banks were failing. This was not due to actual losses, but due to confidence. Banks fail because the market loses confidence in them and deposits flow out. Banks can only survive for so long during a massive outflow of deposits. They can receive emergency liquidity from their central bank, but this is typically against collateral – which has a natural limit.

There is a creditor hierarchy enshrined in law – equity holders rank below bond holders.

For Credit Suisse, language in the AT1 bonds stated that the AT1s could be written down if the bank took capital support from the state. This makes sense in terms of the creditor hierarchy – if the Swiss government had injected fresh capital into Credit Suisse, then shareholders would have been crammed down, meaning they would have been wiped out before AT1s then got written down as a result of the state’s capital injection. What in essence happened over the course of the ‘rescue weekend’ mid-March 2023 is that there was a subtle law change which stated AT1s could be written down if the bank took liquidity assistance from the central bank. This is purely funding, not capital. Borrowing from the central bank causes no cram-down of shareholders. We can ask ourselves why this happened this way. Why did the Swiss government not simply inject some equity to cram-down shareholders, before then writing down AT1s? Factually, there were middle-eastern governments which had invested tens of billions in Credit Suisse shares over the preceding months and years. In the end, CHF16.5bn of AT1s were written down to zero, and UBS then paid CHF3.5bn to the bank’s shareholders.

In Credit Suisse’s case, AT1s were written down and equity not. This was a shock and what’s more, it did not follow the rules of what should happen in a failing bank situation. There was an initial panic in the AT1 market, before it was realised this was a specific Swiss situation. Prices dropped, yields increased, but then calmed down relatively soon after. But a level of fear remains hanging over this sector.

Why the Credit Suisse situation was fabulous though, was that on the Monday after the failure weekend, both the EU and UK supervisors made clear statements that AT1s getting written down before shareholders were wiped out, could not happen in their jurisdictions. In reality, a sovereign state like Switzerland can indeed change rules quickly in any emergency situation. For the EU to change a regulation, it would require twenty-seven countries to come together, with the European Parliament and Council needing to negotiate and agree on a text that the European Commission would draft. This process takes months.

Credit Suisse AT1s should have been written down in any case, as the bank was failing. The fact that shareholders were not, does not change that fact, in our view. Many potential investors in AT1s are still frightened of the sector, keeping yields higher than otherwise. For those who truly understand the risks, this is a positive thing.

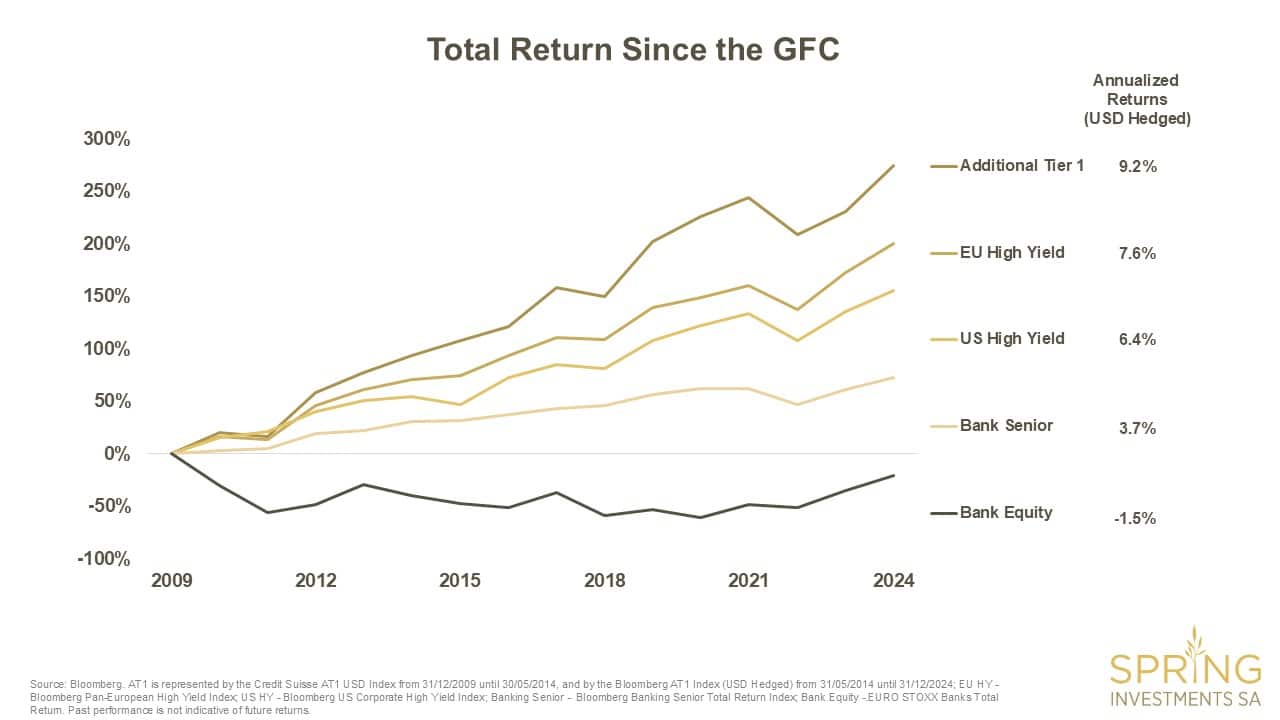

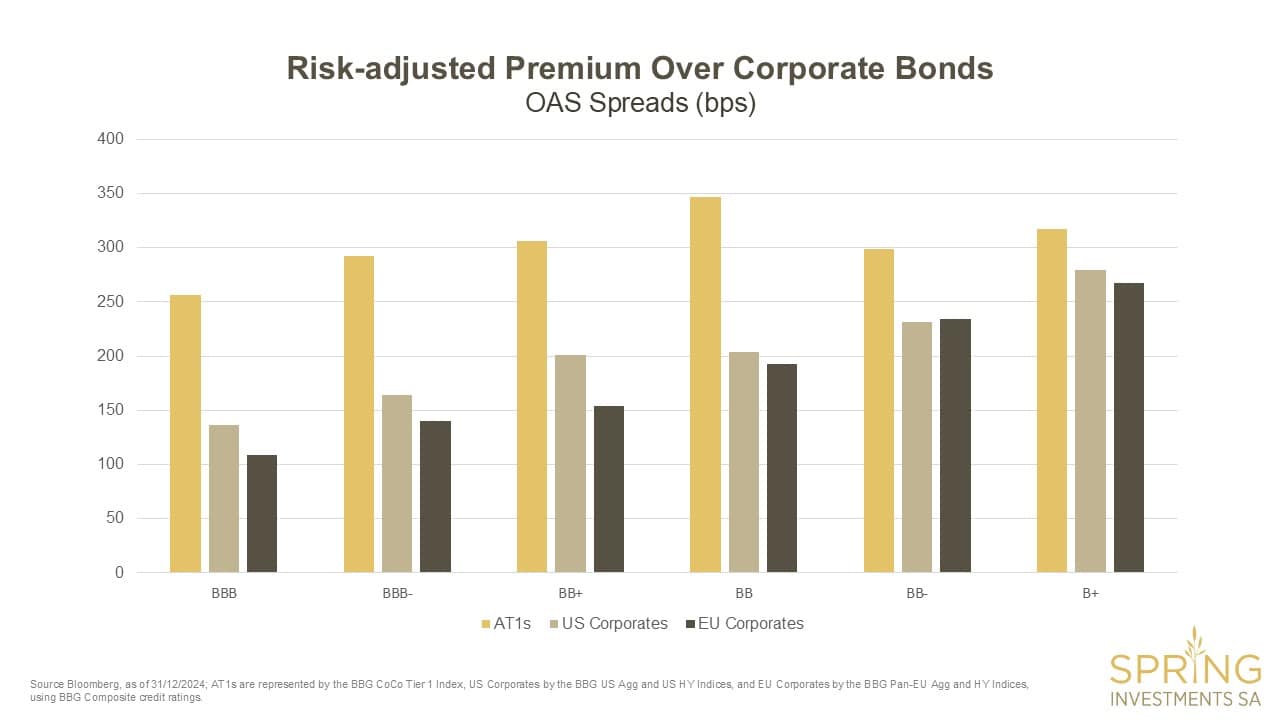

Taking end-2024 yields and spreads, AT1s remain a low-credit risk and high-yielding investment. The exhibit below shows annualised returns versus high-yield corporates, European bank senior debt and European bank equity.

Much of AT1s’ outperformance of high yield (HY) corporate debt – despite a large portion of the AT1 sector being investment grade rated – can be attributed to the inclusion of HY corporate bonds in many asset managers’ benchmarks. Global high yield funds are forced buyers of HY corporates. AT1s are not in their benchmarks, hence yields remain higher than lower-rated HY corporate bonds. We do not expect this to change.

The regulations are complex and can be intimidating, the structures are far from simple, and what happened with Credit Suisse frightened a great many investors away. What remains is a tightly regulated and relatively highly-rated sector with far higher returns than high yield corporate bonds, only two defaults in fifteen years and a market size growing to around a quarter of a trillion dollars.

+41(0)22 736 55 68 | co*****@sp*******.com | 7 Avenue Pictet-de-Rochemont, 1207 Geneva, Switzerland

+41(0)22 736 55 68 | co*****@sp*******.com | 7 Avenue Pictet-de-Rochemont, 1207 Geneva, Switzerland

© All Rights Reserved. No content or images may be used without permission Disclaimer